Courage entails an internal dialogue: a dialogue in which – regardless of what conclusion we reach – our thinking and emotions encounter tensions which put at risk the stability of fundamental aspects of the self, threatening our sense of internal balance. For this reason, courage is not a simple reaction. It requires an integrative process in which there is a risk of losing something, although we often feel that dizzying and heroic sensation following actions that we label as brave. «Blind faith» may be the seed that, as it develops, helps us deal with more complex and internal fears that will require less impulsive actions.

Courage implies the possibility of losing something, or someone, that offers us a sense of vital physical, emotional, psychological or social safety. Frequently, the fear of losing or breaking any of these aspects of our being makes us defend ourselves and instinctively, we deny reality. That is why as we work through our courage we acquire a greater capacity to perceive reality, either in relation to our feelings, thoughts and deeper desires, or in relation to how we perceive others and the world around us. We develop courage and this capacity to face reality by reflecting and containing our own contradictions instead of denying them and attributing them to other people.At times, resolving an internal conflict and facing our fears means staying still. At others, it means taking action.

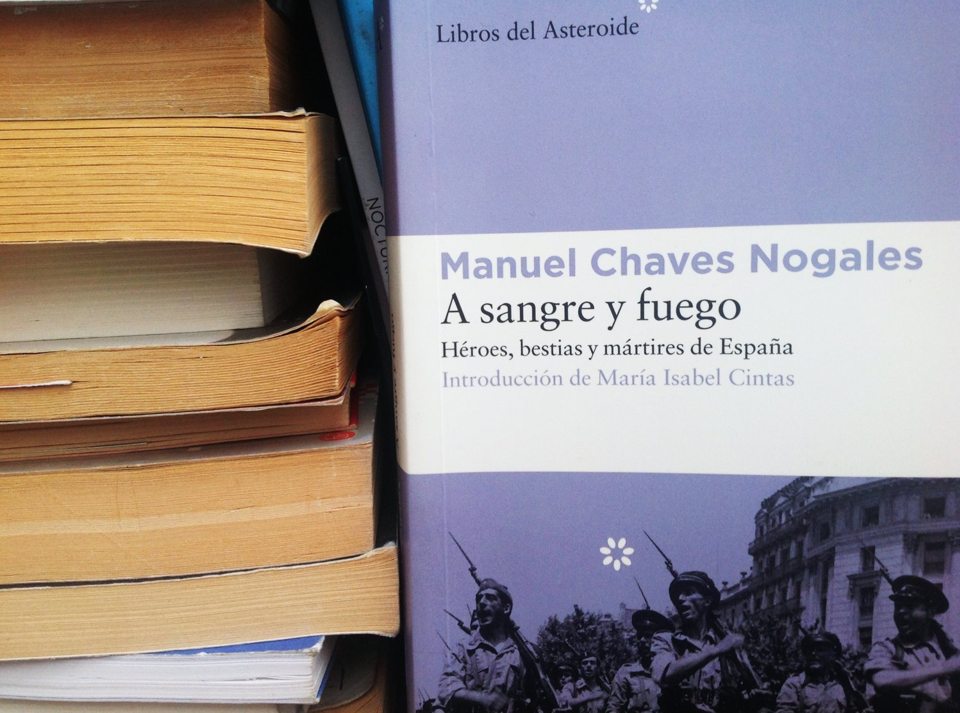

The Spanish writer and international journalist Manuel Chaves Nogales (1897-1944) offers a powerful example of courage. Recently rescued from oblivion by the writer Arturo Pérez Reverte, Nogales had to leave Spain to save himself from the threat of both sides during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), and ended up dying in London during his exile after years of separation from his family.

The courage of Chaves Nogales consisted in describing reality as he lived it, without intermediaries, and making a deep analysis of the human being, independently of his ideological orientation. Pérez Reverte has described him as an «ecuánime» journalist —a Spanish word which can be translated as fair/unbiased/impartial— the opposite of an emotional and intellectual avoidance of the equidistant. Contrary to what some may believe, equanimity does not originate in cowardice, and it does not seek security in others by creating sides. Rather, it originates in freedom of thought, the ability to accept emotional conflicts and describe them as they are without the need to identify with them. Chaves Nogales not only wrote with an immense sensitivity and literary capacity but it seems he was not carried away by opportunism or driven solely by his own psychic complexities. He wrote with a moving courage that denotes his ability to empathize with the pain of others.

As Chaves Nogales wrote in the introduction of A sangre y fuego: Heroes, beasts and martyrs of Spain, ‘war and fear justified everything’. Courage, however, is not justifying or resigning, but in its long journey of seeking truth it tries to accept reality, even if this means a confrontation with our internal monsters.

Ana Rivadulla Crespo (Spain). She lives and works in London as a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist and as a Psychodynamic Psychotherapist.

English Editor: Kate Mills (United Kingdom). Editor. She lives and works in London as a Child and Adolescent Psychotherapist.