.

A proposed handful of words to give meaning to, led to an exquisite journey of poetry by Maia Elsner.

.

Family

.

March 13th in Michigan

.

I sit in my mid-West apartment

amid another snow stormwarning

.

A friend once said winter

is a time of preparation. I was

.

crying. The abrupt sting of thinly

chopped onions blurring white

.

the jagged undersides of branches.

Watch for the swellings, she said,

.

knobbled beginnings before the burst –

soon the blood-streaked magnolia,

.

& who are we not to notice? In the city

my grandfather fled, there is war

.

again. There were other borders

then & names for dandelions wetly

.

opening. I add turmeric, simmering

this gust of yellow-gold. Outside,

.

the crystalline night turns to slip cold

ground, slays what buds of fragile

.

hope, leaves behind a hemorrhaging.

.

.

Symbols & cochineal wings

.

I think of the price of transformation: the grey cochineal insect, its soft body, delicately feeding, tentative between the spines of the nopal.

How despite thousands of small sucking mouths, the ear-shaped slabs of the cactus swell, angling towards the sky, & prickly pears bloom, like tufts of hair, but pink as painted lips.

There are many kinds of bodies, strewn across the desert landscape, attempting to arrive.

The female cochineal have no wings, no means of flight when the careful hand of the harvester lifts to brush them swiftly from the thick green cactus they have made their home.

They will not feed again, but are dried & crushed to dye deep purple-red the thin threads that weave together human things – clothes, our outer casings.

No longer grey, it is as if what remains of the cochineal is the memory of their life-blood – something brilliant & alive.

It takes 70, 000 insects to make one pound of cochineal dye.

.

Fairy tales

.

Variations

.

There is a house by the lake. Every day

a girl exits & sits, knitting by the edge.

.

Perhaps it is the water that inspires her.

Perhaps the murmur of the wind. In all

.

versions, the wind has a voice. Often,

it is a spirit, searching for the body

.

buried in the snow. It explains, there is

a temperature to separation. How cold

.

severs capillary from capillary. Listeners

understand this as metaphor; they too

.

are searching for themselves. Sometimes,

the lake is not a lake but a river. Almost

.

always it is a body of water. Our bodies

hold the same concentration of salt

.

as the sea. Maybe she is not knitting, but

singing the threads of her yearning

.

to the waves. Maybe today the river god

will hear her; maybe there will be no

.

flood. Her brothers have disappeared

as swans, fleeing to warmth. In one report,

.

she provides what they need to survive:

white coats for camouflage. The birch

.

is bare, & the woods’ arms are stringy,

lopsided. In this setting, the swans

.

become human again. The boys will live

another year, will learn to fish, to flush

.

away what threatens: evidence of their

existence as swans. The villagers, unkind

.

to what they do not understand, stockpile

guns. Sometimes the storm comes.

.

Sometimes, sister & brothers are alive

only as long as the story lasts. In defense

.

of fairy tales, is this enough?

.

Zoo

.

In my collection overrun by wild boars, I have a poem called ‘Transnational zoo’, which is an exploration of how people are dehumanized by border practices – hunted like wolves, caught like fish, kept in cages, while others describe their attributes.

This made me think of naming, and the problems of naming. In Genesis, Adam ‘gave names to all the cattle, and to the birds of the air, and to every beast of the field’; there is great power in the act of description, & who it is who identifies the thing &, in the process, defines it. Naming is a kind of creation of objects.

Recently, I interviewed the writer Ada Limón, who spoke about how you might call the small bird with a red head tapping on a birch tree a woodpecker, but who is to say that woodpecker does not name herself dancer-between-wind-&-rain-cosmos-in-flight. In other words, how might animals perceive & describe themselves?

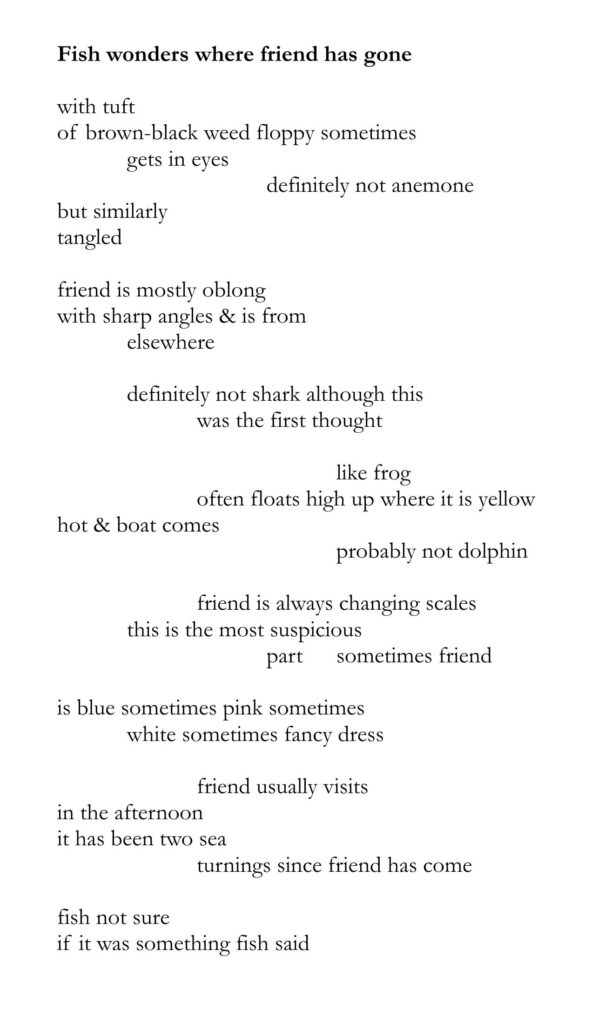

Currently, I am working in a sequence of narrative poems about friendship, set in an occupied territory – which is like a zoo, in that it is policed & boundaried. A boy who comes every day to swim in the sea has disappeared. This poem is from the perspective of a fish, who attempts to describe the human.

.

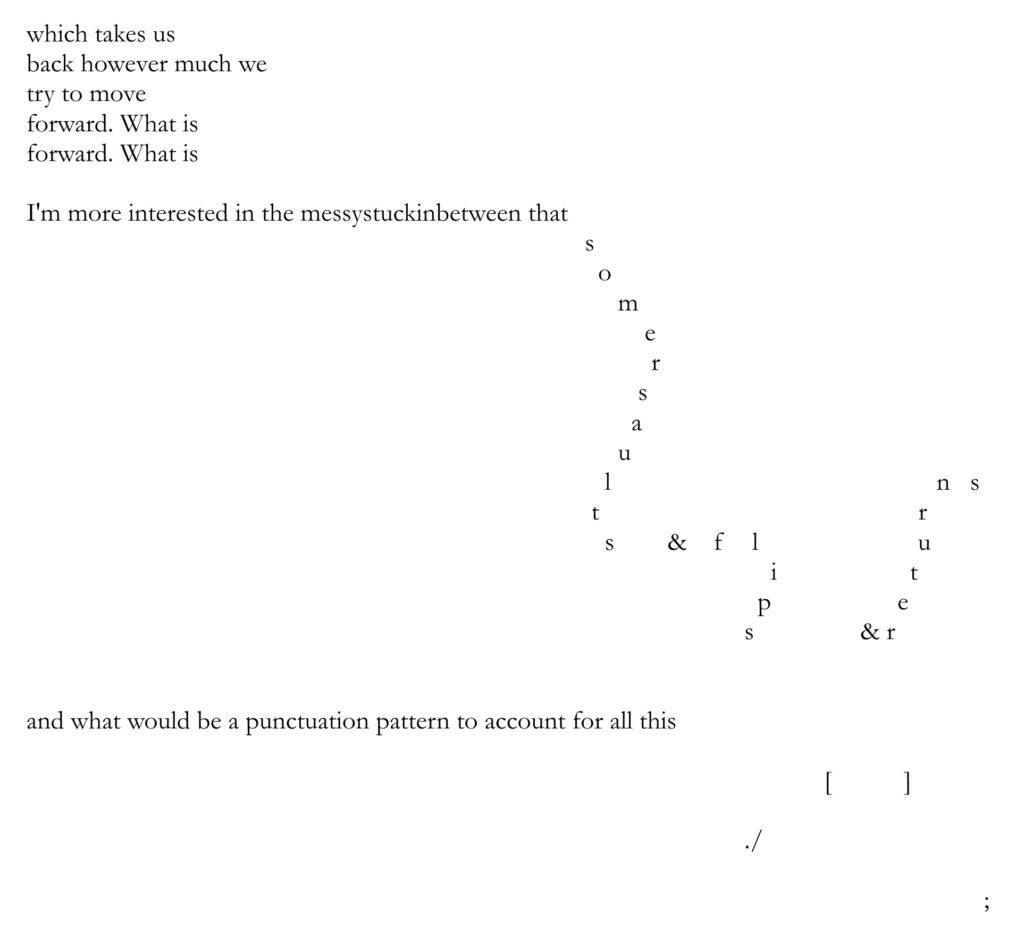

Back & forward

Sometimes I think of prose as a kind of travelling. The traveler – both writer & reader – journeys from an origin point, a past, across the middle-ground of the present, that is always on the brink of becoming, as each eye crosses the no-man’s-land of a typed space to a new word, a new world. This is the promise of narrative. That there is an endpoint, a destination, the possibility of arrival.

This seems to me to echo the idea of linear time, a Western concept, something that is constructed in language and through language, specifically by the subject-verb-object order in English. What would it be like to disrupt that grammar of language & time? To find some syntax to account for its absences & silences? For memory

.

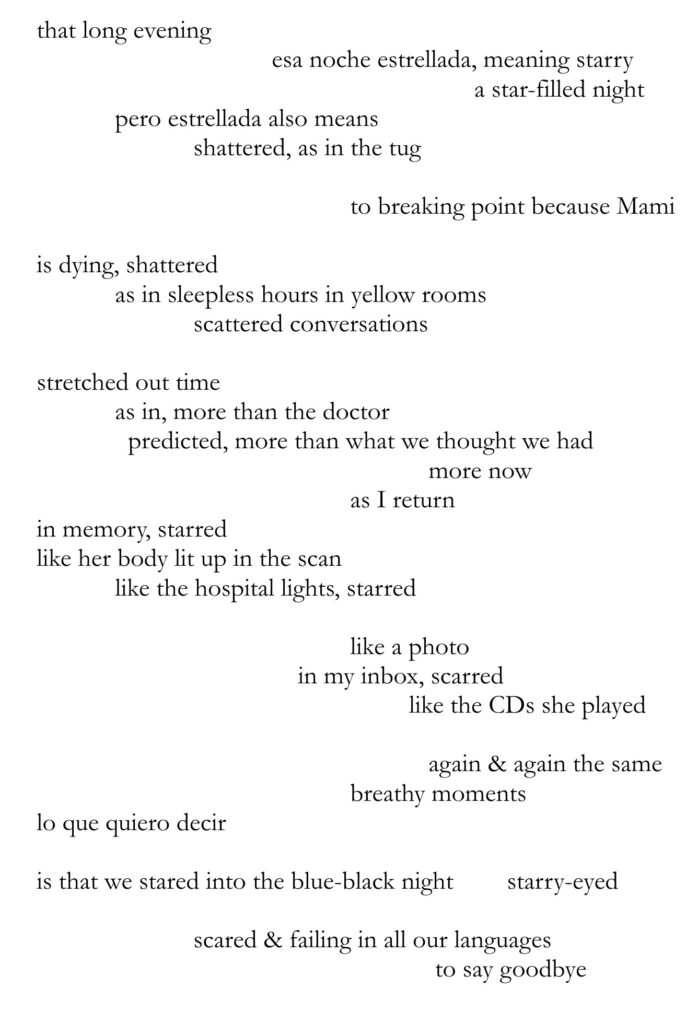

Spanglish

Maia Elsner’s was born in London to Mexican and Polish Jewish parents. Her debut collection, overrun by wild boars, explores the dislocation of lives, objects, and histories through migration and the legacies of colonisation. Most recently she has been involved in a film collaboration with Latin American artists across the diaspora, and in a poetry-postcard project that explores the refugee experience through troubling the line between verbal and visual arts. Her work has been published in British, American, Canadian and Irish journals, and has been widely anthologised. Currently, she is doing an MFA at the University of Michigan.

.

Maia Elsner is participating of Latinx Poetics in Motion at FLAWA Festival on Saturday 14th May 2022 at Rich Mix, London.

Find the full program at FLAWA

Listen Desde la Tundra PODCAST (with subtitles in ENGLISH)